Tubist Eugene Pokorny has enjoyed success at every station in his storied career. He has flourished in some of the most demanding brass playing communities and is a Titan of the tuba world and a first class musician. As a soloist, with brass ensembles large and small, and with some of the finest orchestras in the world, Pokorny has plied his craft with humor, warmth and greatness. It is not an easy to follow a Titan such as Arnold Jacobs, nor to take your place in one of the most storied low brass sections of the past 60 some years. To do so without skipping a beat is remarkable. An alchemist of sound, his tone has adapted to the new CSO to create the signature blend that is at once present without being obtrusive, warm yet clear-genius! The “Fourth Valve” tm is delighted to host the master alchemist of sound, the sensational Eugene Pokorny-enjoy!

1. Charles Vernon, has stated that it might surprise people to know that Jacobs, Kleinhammer, Crisafulli and Friedman were, “four different styles of playing, all going for a similar result.” Now with yourself, Vernon, Mulcahy and Friedman, the resultant blend seems to have all the characteristics of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra with different players. How did you achieve the blend which is so present (and yet can be so supportive of other timbres), with almost a whole new team? How do your sound and Mr. Vernon’s sound in particular achieve such a beautiful blend that is reminiscent of Jacobs/Kleinhammer?

There is a willingness of the sections’ players (some more than others) to subjugate their own personal playing style to one which is more in keeping with the majority opinion. However, there is occasionally some discussion as to where the final sound result will be.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MhHwr1tLrrY

We are all different players with different abilities to adjust to others as well.

I found in my own listening that Jacobs was very lucky to have a musician as competent as Kleinhammer as a sidekick because Kleinhammer would complement his own sound to Jacobs’ playing style, rhythmic proclivities and interpretive rigidity. But that is another subject. For me, the teamwork aspect of playing in a section is the highest goal.

When I play with Charlie [Vernon], I try to find a sound that complements his array of colors. He is more enamored of the lower harmonics in the sonic spectrum of his sound. So, I will try to emphasize the higher side of the harmonic spectrum when I play with him.

Charlie is quite sensitive to the quality of sound when he listens to me trying out different instruments. I find his input very helpful. When we are working on balancing the section, I need to tell him when I (and perhaps others) simply cannot keep up with the output wattage of a bass trombone. The range of all our volumes has to vary from being barely audible all the way to “hell bent for leather†as my hero Jeff Reynolds used to say. We have to have the capability and, more importantly, the willingness to do it all. I have no answers as to the “how†the of the blend that occurs between Charlie and myself.

2. When you take a breath, on most occasions, do you release it immediately in rhythm, or hold it-no matter how slightly? Why or why not?

On most occasions the breath always moves in rhythm both in and out with no delay. If the first note I am to play is in the mid to high register (as in the solo in “Petrouchkaâ€), I may delay to make sure that I am “up to pressure†before releasing the air.

3. Do you conceive of an articulating tongue along the same lines as Arban, where it is a valve that completely albeit temporarily seals the air, or as denting the air stream (Remington), or creating turbulence (Marcellus)?

I think of the tongue as floating above the air stream. When an articulation is needed, the tongue dips into and interrupts the air stream for as long as it needs to then springs back up floating on top of the air stream. When a note is meant to end, the tongue should have no participation at all, except when the notes are meant to be very short. In that case, I will stop the tone with the tongue. Please do not burn me at the stake for saying that. It works for me.

4. What differences did you notice about playing in the CSO when you first joined, as compared with your previous orchestral experiences? Style, attitude, preparation. Do the members listen more?

I need to gauge my answer with the reality that I joined the CSO when I was 36 years old and was still learning a lot about my own playing. However, the biggest physical change was amount of sound output I was expected to produce. This not only meant the loudness but the softness as well. Both Jay [Friedman] and Charlie [Vernon] can play very soft. So can Michael [Mulcahy] who joined the Orchestra several months after I had been there. All three of them could offer a complex array of dynamic contrast. That factor and the dead, dry acoustics of Orchestra Hall make for a very challenging physical environment in which to produce music especially because the resonance in the room itself is practically non-existent.

I estimate it took me most of a season to get up to the volume levels I felt were necessary to pull my weight in the section. The hall in St. Louis where I previously worked had a wonderful resonance in the low register. There was no need to play very loud because the sound was always present and beautiful. The trombone section did not have to be over-amping in St. Louis because there was no reason. We “let†the sound happen in Powell Hall in St. Louis as opposed to having to “make†the sound happen in Orchestra Hall in Chicago.

Regarding style, preparation and attitude every performer in every orchestra is a little different. Some are very conscientious and others are not. As examples of players with great attitudes, I could site Susan Slaughter, Daniel Gingrich, David Herbert, Rick Holmes, Steve Williamson, Richard Lesser, Christy Lundquist, John Hagstrom and some others. Most of these players (from the orchestras in Chicago, St. Louis, Utah, Israel, etc.) are either retired or have passed on. Many of these same players also qualify as ones who prepare their music ahead of time. There are other players who have special qualities. Jeff Reynolds (former bass trombone, Los Angeles Philharmonic) is one with whom I always learned something every time I would sit next to him. Michael Mulcahy (Second Trombone, Chicago Symphony) is one whose musical interpretations would be unpredictable but I know would always be adventurous. Cynthia Yeh (Principal Percussion, Chicago Symphony) would always produce a sound better than the one I would last remember.Do the players listen more in the Chicago Symphony? Some do.

5. Connie Weldon and the tuba quartet, R. Winston Morris and the tuba ensemble, Jacobs and the Chicago Symphony Brass Quintet & CSO Low Brass Quartet/Quintet. How important was chamber music to you, and how do you advise your students to partake?

While playing in chamber music is useful, it is not something I have gone overboard with encouraging students to do. There are very practical reasons for playing in tuba ensemble in terms of playing in tune and adjusting pitch to a “mean tone temperament†(lowering major 3rds, raising perfect 5ths, etc.).

My favorite ensemble in which to play is trombone ensemble. We at one time did that a lot in Chicago but it rarely happens these days. We always manage to put together a trombone/tuba ensemble at the Pokorny Seminar in Redlands during the summertime. I think players benefit in being able to hear individual lines especially when there are fewer of them to listen to in a chamber group.

And who says a low brass player could not play the cello part in a string quartet without great benefit to….well…..the low brass player.

6. How do conceive of or describe the ideal tuba sound? Can you address it in terms of core and breadth.

It is difficult to accurately describe a sound with words and actually know what that sound is. My all time favorite tuba sound is the one produced by Roger Bobo. It was all muscle and no fat. Ideal. Sinewy. Tommy Johnson produced a sound that had heart and depth. It also was a sound I could more easily emulate because of the physical structure of my face, sinuses, etc. David “Red†Lehr has the most awesome, smooth, legato I have yet to hear on a tuba player. I am not sure how to describe any of these players’ sounds in terms of “core†or “breadthâ€. Maybe the previous desciptions will help.

7. What percentage of the time do you estimate that you use the following breathing strategies and why:

A. Take in the breath and release it by simply allowing gravity and the relaxation of the intercostal muscles and diaphragm to allow the air to leave your body in relaxation.

If I am playing Wagner, Prokofiev or any low register tuba parts, I will let gravity do the work for the most part. That would be at least 90% of the time. When I get to the end of my breath capacity I may have to push a little to keep the air moving out, but then I inhale and let gravity do its magic again.

B. As above, but also bringing the stomach muscles in to speed the exhalation of the air.

B. As above, but also bringing the stomach muscles in to speed the exhalation of the air.

GP: Even when playing Wagner, Prokofiev and the other low register tuba pieces, I often must push a little to keep the air moving out, but then I inhale and let gravity do its magic again. As a mantra I try to remember that the “free exchange†of air should be a priority when breathing. The more warmed up and “elastic†I am regarding breathing, the more air I can easily move. Percentage-wise, I would have to say that I eventually start pushing nearly 100% of the time.

C. Placing the diaphragm and stomach muscles is isometric opposition to control the flow of air.

I am sure that in notes that go from “f†(below the middle C) and higher my stomach muscles are in some type of isometric stance, especially as the notes go higher. As a higher air pressure is needed, something needs to produce that pressure. While the isometric is not “idealâ€, I am sure it is present as a safety precaution to have ample pressure ready if needed. I think of the aeronautical aspects of landing a plane with the engines spooled up ready to “pull up†again in case of a problem.

7. From your vantage point inside the orchestra, are there any composers for whom your admiration only grows?

When the orchestra plays opera (which is rare for us), the repetition builds up expectations and my attitude improves (usually) when I have to a chance to play or listen to the music multiple times. Prokofiev and Wagner are always a great adventure to get exposed to. The writing and orchestration of Ravel is always revealing something new to me. I am enamored of some music my colleagues would scoff at, for example, Ferde Grofe’s “Grand Canyon Suite.†Outside of the orchestra, the music of Puccini and Gerald Finzi are now my greatest loves. I am much more moved in significant ways by Finzi than anything I have ever heard by Mozart. [Now you can burn me at the stake, but I will not retract that statement.]

c. 2016 David William Brubeck All Rights Reserved www.davidbrubeck.com

images courtesy of

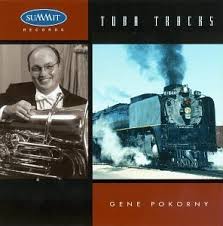

Eugene Pokorny

USC.edu

Summit Records/amazon.com

University of The Redlands

Interested in more “Fourth Valve” tm interviews?

Don Harry

John Stevens

Jim Self

John Van Houten

Demondrae Thurman

Deanna Swoboda

R. Winston Morris

Beth Wiese

Beth Wiese

Aaron Tindall

Marty Erickson

Beth Mitchell

Chitate Kagawa

Aaron McCalla