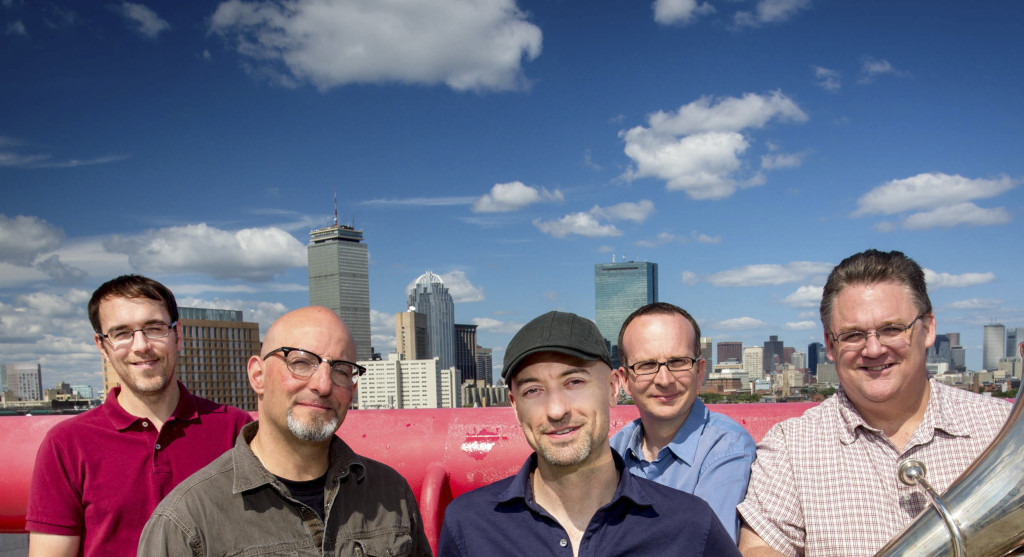

1. The Atlantic Brass Quintet is a remarkable group comprised of five multi-faceted and intriguing individuals. How did you manage to come together, and more importantly, stay together?

SETH: We stay together based on respect and mutually shared goals. Our tuba player, John, says “Some guys go on hunting trips to have fun. We go on ABQ tours!” There’s just so much trust in the group that both rehearsals and performances are just incredibly fun!

MANNING: I would agree with Seth and say that the critical ingredient to a successful group is a mutual respect for your colleagues. We first formed in 1985 at Boston University under the tutelage of the Empire Brass Quintet. They had a thriving brass chamber music program and each semester, all brass students were formed into chamber music groups. The Empire Brass hand-picked the members of the Atlantic Brass Quintet and got us our first gigs. The Atlantic BQ have had several personnel changes over the years – which is inevitable – but have always managed to maintain a high standard for our performances and recordings. I think what keeps us together is that we find that the musical experience is extremely rewarding and inspiring. This September will mark our 30th anniversary, and we hope to be going for another 30 years!

MANNING: I would agree with Seth and say that the critical ingredient to a successful group is a mutual respect for your colleagues. We first formed in 1985 at Boston University under the tutelage of the Empire Brass Quintet. They had a thriving brass chamber music program and each semester, all brass students were formed into chamber music groups. The Empire Brass hand-picked the members of the Atlantic Brass Quintet and got us our first gigs. The Atlantic BQ have had several personnel changes over the years – which is inevitable – but have always managed to maintain a high standard for our performances and recordings. I think what keeps us together is that we find that the musical experience is extremely rewarding and inspiring. This September will mark our 30th anniversary, and we hope to be going for another 30 years!

2. There seems to be a significant reservoir of freelance experience in the group which recalls The New York Bras Quintet. Have you come across any commonalities with that group? Which chamber music groups have influenced you?

SETH: Some of our early sound concepts came from Empire. In many ways, we were their apprentices.

We have tremendous respect for a lot of the other chamber music groups out there. I think we’ve had especially close ties to American and Meridian, because we’ve shared players over the years.

MANNING: I suppose most chamber music groups are comprised of musicians who freelance, and I think that the collective experience of our current members represents a rich and varied set of influences. From symphonic to jazz, Klezmer to hip hop, we bring to the table a well-balanced and broad collection of musical experience. I think this diversity strengthens our ensemble and make our musical approach more accessible to our audiences.

We have been inspired by the Empire Brass, of course, and we have great admiration for chamber groups like the American Brass Quintet, Meridian Brass Ensemble and Kronos Quartet.

Atlantic Brass Quintet Fenway Recital Sampler 2014

3. This Atlantic BQ has experienced tremendous success in competition. What is that headspace like, and what did you get from your coaches?

MANNING: During the early years of the Atlantic Brass Quintet, the group made it a goal to compete and win in all the chamber music competitions they could – and they did. It was during a short period of three years (while I was in the Air Force), that most of this happened. Between 1986 and 1989, Atlantic BQ won first prizes at the Coleman Chamber Music Competition, the Carmel Chamber Music Society Competition, the Shoreline Alliance Chamber Music Competition, the Summit Brass First International Brass Ensemble Competition, and the Rafael Mendez International Brass Quintet Competition. During that time, the personnel was Joe Foley, Jeff Luke, Bob Rasumussen, John Faieta and Julian Dixon. I rejoined the group in 1989 after all the hard work was done! In 1992 we went to France and won the “Premiere Prix” at the International Brass Competition of Narbonne, France.

In preparation for these competitions, we received a lot of help from our coaches, including Charlie Lewis and Sam Pilafian (Empire Brass) and Roger Voisin (former principal trumpet of the Boston Symphony and head of the Brass Department at Boston University). They were all incredible mentors and teachers and the taught us invaluable lessons about balance, blend, intonation and expression and even addressed stage presence and business advice. As far as “headspace” – I don’t know. We were proud of our achievments and listed them in our publicity, but frankly we just kept going, trying to make the best music we could by continuing to challenge ourselves and engage our audience.

4. Literature aside, is the traditional brass quintet instrumentation the most effective you can imagine? Why or why not?

SORG: I believe the traditional instrumentation is the most effective because it’s closely related to SATB, but the addition of the tuba or bass trombone create a blend and frequency superior to a standard brass quartet. Also practically speaking, a quintet’s general business fee is more marketable for standard gigs, than a larger ensemble.

MANNING: If you are referring to tuba vs. bass trombone, I suppose I might be a bit biased toward the tuba – and I will admit I generally prefer that color and depth at the bottom of the group. That said, people like John Rojak prove that a great bass trombone sound is just as pleasing. There are some works in the repertoire that were written for the bass trombone, and I would much prefer to keep those works that way. We’ve also been impressed with how well many of our bass trombone students in the Atlantic Brass Quintet Seminar handle the “tuba” parts with agility and depth of tone.

The challenge that most homogenous groups face is to prevent the audience form getting color bored – that is, always hearing the same instrumentation throughout the duration of a recital. Our trumpet players mix it up a lot, switching from piccolo trumpets, B-flat and C, and Flugelhorns. Mutes, how the group sits or stands, extended techniques and clever arranging can also help.

5. How do you guys handle the division of labor?

SORG: Five ways!

SETH: Everyone has duties. I’m the financial guy. I pay the bills and try to keep the books balanced. I think it just highlights how much the modern musician needs to have a variety of skills.

MANNING: Everyone contributes in one way or another. One person is the liaison between our manager and the group, another deals with travel, another finances, another CD sales. Some members of the group contribute through arranging and composing. Sometimes there are small one-time tasks, and other times there are large projects that we all chip in to get done. To keep a group running, there is so much to do beyond practicing your part and showing up to rehearsal.

Andrew Sorg,

6. Hip Hop and Chamber Music! How and why do they meet? What doors has it opened?

I grew up very sheltered, musically speaking. I missed out on all classic rock, rock n roll, 80’s cheese, heavy metal, grunge, etc. But I did have a great classical, jazz and hip-hop influence in my childhood. Growing up in a urban neighborhood with a strong NYC presence, was all about rap and hip-hop. My high school trumpet section would take turns free-styling on our band trips and car rides, it was and is a part of who we are.

I was very inspired by this to experiment with creating hip-hop beats, lyrics and songs. Writing over 40 hip-hop songs, some with mixed meter beats, taught me how to compose. This hip-hop feel of my compositions can easily be heard in my two brass quintets, Mental Disorders and Voices In Da Fan. As far as doors opening…the brass community has embraced my compositions and students from various universities are even performing them. I have received a lot of love from not only brass players, but audiences as well. However, the hip-hop community has not yet embraced the art form of ‘mixed-meter hip hop’ and has slammed some of those open doors right in my face!

7. Your career evidences the most “dyed in the wool” brass quintet devotee. What do you see the brass quintet genre exploring in the next 40 years?

There is so much I could say about this…It would be my hope, that the brass quintet continually breaks musical ground to become a full platform for individual and group expression, outside of the general business idiom. The brass quintet can be, should be and is more than a gig band for graduations, weddings and ceremonial events. I believe more brass players will be composing, performing and recording their own pieces, hopefully with a personal emotional message to connect and share with their audiences.

I believe more multi-media works will be explored as well as brass quintet and electronics. It’s always been a dream of mine to have a brass quintet hooked up to a real time midi sequencer, with endless options for sound, not just a reverb/echo effect. I believe that we’ll see more collaborations with singers and other instrumentalists/ensembles which will expand the way we use/view the ensemble.

It seems unfortunate, at times, that the popularity of the brass quintet coincided with the that of contemporary music. As a result, many of the pieces actually written for brass quintet were not accessible to audiences’ ears-(and still aren’t!) This seriously hurt our future of being hired to play the music written for us by famous living composers. We need music that general audiences actually WANT to hear. This means the brass quintet needs great new music to play, that connects to audiences ears musically with a story to touch them emotionally. Therefore, the future of the brass quintet lies in the five individuals abilities to be great arrangers, composers and innovators, making sure that their end product, is something that has never been explored before.

Thomas Bergeron

8. Hybrid Jazz Chamber Music. What expressive and audience experiences have you noted?

My goal has always been to encourage classical audiences to realize their love for jazz, and jazz audiences to realize their love for the great classical composers. I believe that the commonalities between the two genres go far deeper than many presenters realize. Audience reactions to my jazz group’s performances corroborate this idea. Presenting, for example, a jazz/improvised version of a Messiaen song cycle, we repeatedly hear things from classical audiences like “I never thought I’d enjoy a jazz performance so much”, and from jazz audiences “I’ve never heard Messiaen’s music before, but now I’m going to go listen to everything he ever wrote”.

The beauty of the cross pollination goes deeper than just audience-building. Musically, jazz players bring the work of classical composers to life in a uniquely vibrant way. Of course, on the surface, there is the improvisational element that extrapolates upon the original composer’s material. But in a more general sense, jazz musicians are instinctually committed to freedom and rule-breaking in a way that allows performances to breathe very openly. In fact, the great classical soloists have this too. Yo-Yo Ma is a great example. I also just heard Anne-Sophie Mutter perform a magical Sibelius Violin Concerto at Carnegie Hall. Her interpretation was so free that it would be almost impossible to transcribe. The music was completely internalized, and was performed as if it was flowing directly from her soul. John Coltrane would have totally dug that performance, and I believe Anne-Sophie Mutter’s mind would have been blown at a Coltrane performance. There’s an idea for a book …

I see our globalized society as increasingly cross-pollinated, and I love presenting music that represents this. That’s one of the reasons why the Atlantic Brass Quintet feels like such a great fit for me. From traditional chamber music roots, the group has developed a voice that truly represents the diverse interests of its members. Jazz is a big part of this (look out for our upcoming Mehldau transcriptions), as is Balkan music, hip-hop, and music from Latin America.

Seth Orgel

9. You were trained by members of the Chicago Symphony. How do you view their concepts and legacy differently as an accomplished professional than you did and a student?

My primary teachers from Chicago were Richard Oldberg, Dale Clevenger and more recently Gail Williams.

My sound concept is still very strongly rooted in the Chicago sound I learned way back in the early 80s. I have to say that every day, either in my teaching or my own playing, I refer back to lessons or skills that I learned in Chicago. Much of the teaching had a lot to do with Arnold Jacobs work. Jacobs approach and style still remains so effective and positive, that I really feel it must be included in the education of young players.

As to the legacy, that’s just impossible to overstate. So many great professional players have come out of Chicago, with teaching backgrounds from those CSO players. Many of my colleagues, both players and college level teachers have that Chicago background. I just feel so lucky to have shared in the tradition and history.

How would you contrast the musical and personal skills required for a symphony job and freelancing?

I don’t think, as a musician, you can overstate the importance of being easy to work with. I think that’s important wherever you work. I feel like my job is to help create the optimal environment in which everyone can play their best. That means getting along and keeping everything as positive as possible. Musical skills for freelancing and symphony aren’t really that different. I think the important thing is to show up really prepared for rehearsals as well as the show. When you sit down to play, especially with others, you want to be able to focus on the music and making music, not notes or other technical things. I guess as a freelancer more sight-reading, and just the variety of situations in which you find yourself, plus travel can be stressful. It’s hard to beat the great symphonic rep. Pretty much any performing as a player is just great.

Tim Albright

10. Top flight jazz and classical careers such as yours are rare. Were you inspired by Wynton? Were you disappointed when he put aside classical music?

I wouldn’t say that they are necessarily rare. Especially these days with the talent pool so high and the gig pool so small, I see more and more brass players that are outstanding in more than one genre, sometimes out of shear financial necessity alone.

There were two defining moments in my musical life that lead me to my dual identity as a performer. The first one was when I was in grade school in St. Helena, CA and I got to see the local high-school jazz band perform. (Incidentally, my older brother and sister whom I adored where playing in the band.) That music hit me like a ton of bricks. I had this wonderfully giddy feeling that left me somewhere between laughing and crying in my seat. The second moment was during my first rehearsal as a member of the San Francisco Youth Orchestra. We were playing Brahms 1, and the trombones don’t play for the first three movements. As the rest of the orchestra read through the opening of the first movement, I was again floored. My body physically reacted to the power of the music surrounding me. I’ve been chasing that feeling now for 30 years.

Although my older brother played trumpet, I was very much a trombone geek when I was younger. I transcribed J.J. Johnson records and Joe Alessi records with the same fervor. I distinctly remember hearing my brother’s copy of Wynton’s record “Standard Time Vol. 1” and I remember being aware of his amazing piccolo-trumpet playing. And, I remember hearing people quote Wynton as saying that jazz gave him a much better ability to express himself individually, and that is why he gave up classical music. I don’t know if he actually said that, but I understand the sentiment.

There is sometimes the notion that as classical musicians, we don’t have as much personal input in performing a work written by someone else. After spending several years as a member of the Atlantic Brass Quintet, I can say that there is a TON of room for personal input, but perhaps it’s on a smaller scale. To relate it to visual art, it’s almost as if in the quintet we are putting together all of the little dots in a Georges Seurat painting to create the larger work. Put those dots in a slightly different spot and you have a wildly different painting. In jazz, I feel like I’m using broader strokes, but the emotional dividend is the same. In the end, I’m still just trying to find that giddy feeling between laughing and crying.

11. How does nature inform or inspire your artistry?

I grew up in more or less rural California surrounded by hills, rivers and vineyards. I spent my summers in the redwoods. I took boy-scout and school trips to Yosemite, Grand Canyon and many other breathtakingly beautiful places. I took that all for granted because it was what I grew up with. It wasn’t until I had gone away to college and came back that I realized how amazing that landscape really is. My wife and I lived in Brooklyn for several years, and although we still miss the tireless energy of that borough, we both realized that we needed some nature in our lives in order to survive.

We now live in Croton on Hudson which, as the name implies is on the Hudson River north of New York City. We live a short walk away from beautiful parkland, and we both feel like we can breathe a little more now. (You have to understand, in the summertime it stinks in New York. Literally stinks.) I remember going for a run on a spring day in Croton and yelling out loud “it smells amazing here!” The neighbors must have been a little frightened. I need nature for day-to-day survival, not just for inspiring my music. Living in the city, it can be easy to forget that we are all connected; we are all part of the earth.

Atlantic Brass Quintet Second Half Highlights-mp3

John Manning

12. You have performed with Empire Brass some as well. What was it like, and what did you take away from the experience?

In the mid-1990’s I was asked to play some concerts with the Empire Brass. They were our mentors and inspiration, so it was a great honor. It was at a time when Sam Pilafian, my teacher, was exiting the group, so although it was an honor, it was also pretty intimidating. There was no way I could fill his shoes, but I did my best. I played concerts with them in Texas, New Mexico and Nantucket, and it was always thrilling. The programs were challenging and the music making top notch. I learned a lot about preparation, programming and interacting with the audience. Sam’s teaching and playing continue to inspire me and I will never forget how grateful I am to him and the original members of the Empire Brass for their inspiration and guidance.

13. You seem drawn to eclectic travels and music. What has opened your eyes and inspired you?

I think since the first time I traveled abroad with the Greater Boston Youth Symphony Orchestra I have been fascinated with the fringe benefit all musicians enjoy – traveling to different places and cultures and dropping in on their worlds. With the Atlantic Brass Quintet, I’ve had the opportunity to travel to 48 states and 15 countries around the world, including: France, England, Guatamala, Panama, Costa Rica, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Pakistan, India, Saudi Arabia, Oman, Yemen, Kuwait and Egypt.

Our most exotic adventure was a tour of the Middle East, sponsored by the US State Department in 1995. It was a six-week tour with about 25 concerts in 7 countries. It was very exciting – at times grueling – and we were exposed to many different cultures. We also learned to appreciate how fortunate we were and realized how much we appreciated our own country. We met some beautiful people, witnessed some sad situations, and were amazed at seeing places like the Taj Mahal and the Great Pyramids of Giza. Seeing millions of homeless people in India and experiencing the amazing culture of Japan were two eye openers for me personally.

The quintet has given masterclasses throughout Central America, and I have been to Argentina twice recently and worked with many students there. I have found the talent and thirst for knowledge of these students inspiring, especially with limited resources. I sometimes think that American students don’t fully appreciate how many resources they have available to them. I try to instil in my own students an appreciation for what they have and encourage them to utilize all of the tools at hand.

c. 2015 David William Brubeck All Rights Reserved. davidbrubeck.com

Interested in more “FIVE” tm interviews?

Canadian Brass 2014, Windsync 2014, Boston Brass 2015, Mnozil Brass 2015, Spanish Brass 2014, Dallas Brass 2014, Seraph 2014, Atlantic Brass Quintet 2015, Mirari Brass 2015, Axiom Brass 2015, Scott Hartmann of the Empire Brass 2015, Jeffrey Curnow of the Empire Brass 2015, Ron Barron and Ken Amis of the Empire Brass, Meridian Arts Ensemble 2015, Berlin Philharmonic Woodwind Quintet 2015, American Brass Quintet 2015

>